Juliet: ’Tis but thy name that is my enemy;

Thou art thyself though, not a Montague.

What’s Montague? it is nor hand, nor foot,

Nor arm, nor face, nor any other part

Belonging to a man. O! be some other name:

What’s in a name? that which we call a rose

By any other name would smell as sweet;

So Romeo would, were he not Romeo call’d,

Retain that dear perfection which he owes

Without that title.

Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet, Act II. Scene II.

So it turns out, quite a lot. That’s what’s in a name. Our response. Our attitudes. Our history. Our background. Our imperfections. Our desires. Us. We transpose ourselves on to the name, the thing, the semblance of our perceptions. We sign the signifier and in doing so give it a meaning, our meaning, our relationship with that name.

Tonight I watched Colin Firth expertly play Max Perkins in the film Genius with Jude Law as the author Thomas Wolfe, a film based on A. Scott Berg’s biography Max Perkins: Editor of Genius recounting Wolfe’s first publication, Look Homeward, Angel, originally titled “O Lost”. There’s a beautiful quiet somnolence in Firth’s character and his gentle, unforced mannerisms when he suggests that the last time has come to rename the massive literary work.

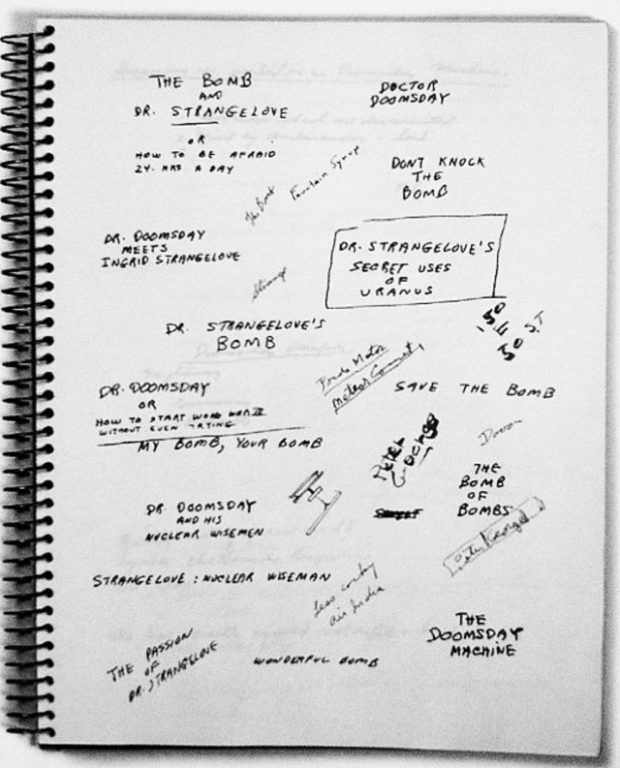

Later, whilst grazing on electrons, I chanced via a circuitous route, on an image of the various names by which Dr Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb might have been titled:

Yes, what is in a name? A very great deal. What is in a word, a phrase, a sentence, a paragraph, a novel? A feeling, a desire, an interpretation of our existence. What sense is there in existence? Precisely that. Whilst the Montagues and Capulets duke it out over an ancient grudge their names have meaning, as too does Look Homeward, Angel and Dr Strangelove, we lay our own scene in the Verona of the mind selecting our words carefully, and our names with rigour, we hope, lest the meaning is attached regardless.